Benjamin Franklin’s 1754 version of the iconic reptile.

The “Join, or Die” snake is one of America’s most recognizable, beloved and replicated icons. Emblazoned on flags and t-shirts, pillow cases and iPhone cases, and even on tv show title cards and in comic books, the image is upheld today as a both specifically as an emblem of American independence, and generally as bid for unity against a common oppression. But the world’s most adored reptile didn’t start this way.

Created by Benjamin Franklin in 1754, the “Join, or Die” snake originally signified loyalty to the English empire. It wasn’t a call to action, but an order to fall into line. It was only later that “Join, or Die” evolved into a revolutionary rallying cry — and when it did, it became America’s first meme, too.

Though most of us associate memes with the internet, they predate even the oldest URL. They’re older even than the “term” meme, which Richard Dawkins coined 1976. He wasn’t the first person to take note of these ambiguous, amorphous nuggets: Austrian sociologist Ewald Hering referred to “die Mneme,” from the Greek word meaning memory, in 1870; and German biologist Richard Semon wrote about them in 1904. But Dawkins was the first to sketch out a definition: Memes are, roughly, universally recognized and self-replicating cultural units that relay social codes or values.

“Examples of memes are tunes, ideas, catch-phrases…. Just as genes propagate themselves in the gene pool by leaping from body to body via sperms or eggs, so memes propagate themselves in the meme pool by leaping from brain to brain via a process which, in the broad sense, can be called imitation.”

Later theorists elaborated on this, pointing out that memes aren’t static, nor are humans simple transmitters of memes. Humans shape memes as much as memes shape us. Nor are memes simply tropes and trends. Sure, some are flashes in the pan, but the most powerful memes are longer-lasting and more impactful. According to memetic expert Limor Shifman, the mightiest memes have longevity, fecundity and copy fidelity — i.e., no matter how much they change, their relative meaning remains the same. Mimicked and reiterated so often, the meme becomes, as philosopher Dr. John D. Gottsch attests, part of a culture’s “inviolable canon.”

But while a meme’s meaning may remain the same, their context and connotation can change and can be changed. They can take on or be given new nuances. For example, lynching postcards were a meme that the NAACP coopted to fight racism. (And, on a less cheery note, Pepe was a party-loving frog until Donald Trump’s white supremacist supporters stole him for their own devices.)

Examining the history of “Join, or Die,” it becomes clear that this is more than an image. It’s America’s founding meme: Replicated and imitated over and over in its first years, this visual symbol was turned from a mark of colonial subservience into a badge of proud independence, becoming the beloved icon for a nation that itself became a meme.

To get the full picture, though, we gotta flashback…

⌇ ⌇ ⌇

Benjamin Franklin, Meme Maker:

It’s early 1754 and England was more worried about old nemesis France than usual: their long rivalry was already boiling over in Europe, and now the French had formed alliances with native North American tribes and were incurring on England’s frontier outposts. Parliament tried to dissuade them by dispatching a young general named George Washington to rattle the saber, but this did nothing. The Frenchmen had one thing in mind: conquering British North America. With their own troops engaged overseas, the English decided the best route forward was to deploy American colonists against the French. This was easier said than done.

Not only did untrained farmers have little stomach for the prospect of facing French forces, but the American colonies weren’t particularly prone to cooperation. There was no sense of solidarity from one colony to the next. As Englishman Andrew Burnaby later noted, “Fire and water are not more heterogeneous than the different colonies in North America.” Still, English authorities figured there was no harm in asking, so in early 1754 they sent letters urging colonial political leaders to join forces not just with one another, but with pro-English Indians, too, creating a coalition that could protect the empire’s interest. One of the recipients of this novel invitation was a Philadelphia-based publisher and political named Benjamin Franklin

Forty-eight years old and fiercely loyal to the crown, Franklin had already floated the idea of colonial unity. He argued in a 1751 letter that a “union of colonies” would go far in “proper management” of mutual concerns, including security for the empire at large; and he offered a similar argument in 1753: “It may be greatly conducive to His Majesty’s service, that all his Provinces in America should be aiding and assisting each other…”[i] This invitation was the first step to making his dream of a United Colonies of England come true.

Needless to say, Franklin replied with an eager “Yes!” Other leaders agreed to the intercolonial meeting, too, and ultimately a date and place were set: June 16th, Albany. Be there or be square.

At this point it was early April, meaning Franklin had two months to shore up support the Albany Congress. He knew what needed to be done — classic fear-mongering y — and also how: through his widely-read and well-respected newspaper, The Pennsylvania Gazette.

So, on May 9, 1754, Franklin ran what was then one of the most alarmist op-eds ever written: a screed insisting the French were preparing to “kill, seize and imprison our Traders… murder and scalp our Farmers, with their Wives and Children” Their ultimate end was “the Destruction of the British Interest, Trade and Plantations in America.” And why were the French so brazen? Because the colonies were divided: “The confidence of the French in this Undertaking seems well-grounded on the present disunited States of the British colonies.”

It was a good piece, but Franklin knew it needed something to make it sing, so Franklin capped his column with a woodcut of a writhing snake, its body cleaved into eight pieces, each labeled with a colonial government or region — Georgia was still a proprietor-owned penal colony — and all lurching rightward in unison as the gaping snake commanded, “Join, or Die.”

The first-ever representation of the colonies as a single unit, this image often described as America’s first political cartoon, was a game-changer. Too bad it wasn’t original.

Re-Mix!

Nicolas Verrien’s original version, “Rejoin or Die,” can be seen on the left.

Fun, ironic fact: The anti-French “Join, or Die” was actually ripped off from French artist’s Nicolas Verrien’s 1685 print “Rejoin or Die.” Originally printed in the tome Livre curieux et utile (Curious and useful book), Verrien’s “Rejoin or Die” was then reproduced in 1696 and again 1724. There’s little doubt Franklin came across Verrien’s work while studying linguistic symbolism and later tweaked it for his own purposes. [ii]

“Join, or Die,” was therefore mimetic from the get-go — and now it was about to go viral. Or, at least, the eighteenth-century version of viral.

Snake Spread:

No matter how popular his paper may have been around Philadelphia, Franklin knew he needed to rally allies outside Pennsylvania. To that end, the well-connected editor sent “Join, or Die” and its accompanying op-ed to like-minded editors in Boston, New York, and even London, where he hoped friend Richard Partridge would print it. Partridge didn’t take him up on the offer, but four American publishers did.

The Boston Gazette’s rendition.

Franklin’s former apprentice James Parker ran a “Join, or Die” variant in the New-York Gazette on May 13; and the New-York Mercury did the same that day, too. Boston-based editors also heeded Franklin’s request, though altered it slightly by turning Franklin’s relatively goofy snake into a more aggressive creature: The Boston Gazette’s version, printed on May 21, now had a roaring snake demanding, “Unite and Conquer;” and two days later, the Boston Weekly News-Letter meanwhile replaced “and” with an ampersand to run “United & Conquer.”

South Carolina’s Gazette didn’t include either slogan, nor the original drawing, but it did run a slightly augmented version: the colonies were now represented by simple, non-anthropomorphic dashes, the editors’ way of hiding the fact that Franklin’s original had SC pulling up the rear; and while The Virginia Gazette, didn’t print an image or text, it referred to the already-infamous image as an “ingenious emblem.”

That’s five papers mimicking Franklin’s image in less than two weeks, a pretty significant feet in the pre-internet era. And subtle differences between these woodcuts aside, the meaning remained the same from Boston to South Carolina: Americans must unite into a cohesive entity to defend the motherland.

The seeds for American unity were thus planted. But they wouldn’t grow. Not yet. The French-Indian War broke out on May 28, a few weeks after Franklin first published “Join, or Die.” And even though The Albany Congress came up with a plan for unification and mutual defense, Parliament and the respective colonies rejected it. They would rather fend for themselves than give up the slightest bit of autonomy. Thus, rather than uniting and turning back the French invaders together, ragged regional armies and ad hoc militias fended the invaders off as best they could— for seven years, until the 1763 signing of the Treaty of Paris. Thousands died in the process.

In the end, the French were squelched, the Brits gained more land for themselves; and the Americans colonists went back to being loyal subjects. All was well, men rejoiced, and “Join, or Die” faded away. For now; no one knew at the time, but the seeds for American unity were already germinating.

The Snake Returnssss:

The French-Indian War left England deeply in debt, a debt England tried to pay by passing the buck on to their American colonists. First was the Sugar Tax of 1764. Instantly unpopular, it’s passage unleashed mass outrage, including the first murmurs of “no taxation without representation.” But England wouldn’t hear it; they soon passed another tax, the Stamp Act that put tariffs on all pieces of paper, from pamphlets to newspapers, playing cards to music sheets.

Colonial reactions this time were even more forceful than before: In addition to burning effigies of colonial officials, nine of the thirteen colonies came together for the Stamp Act Congress, a show of rebellious intent that scared the bejeesus out of English overlords. But even more troubling than this blatant and brash confab: A secret society called the Sons of Liberty had been whispering in colonists’ ears, “Join, or die,” threatening shadowy revolt. Among their ranks was one William Goddard.

Later known for steering the Constitutional Postal Service during the war, Goddard was at this point a struggling journeyman journalist who bummed from town-to-town, borrowing supplies from friends and publishing what he could, when he could. It was in this way that Goddard arrived in Burlington, New Jersey. And it was in this way that he asked for some help from his former mentor, James Parker — the same James Parker who had been Franklin’s apprentice. And, yes, this is how Goddard gained access to one of Franklin’s original “Join, or Die” woodcuts. Goddard knew immediately the sassy snake was the perfect mascot for the anti-Stamp Act paper he was planning, The Constitutional Courant.

“The Constitutional Courant” coopted Franklin’s snake.

Published on September 21, 1765, the snake-adorned Courant was more than just the cartoon and “Join, or Die” exhortation. It also hosted a sharp-tongued harangue against The Stamp Act:

“At a time when our dearest privileges are torn from us, and the foundation of all our liberty subverted, everyone who has the least spark of love to his country must feel the deepest anxiety about our approaching fate. The hearts of all who have a just value for freedom must burn within them, when they see the chains of abject slavery just ready to be riveted about our necks.” [iii]

The message and its reptilian emblem spread even faster than in 1754: copies were immediately sent to New York, and when those copies ran out, knock offs were circulated in their stead; reprints of the Courant also made their way Boston, where the separate Boston Evening Post also ran it across their front page. Meanwhile, news of its rebellious nature made its way up to Maine and down to Georgia, too, and wherever people heard, they marveled at the Courant‘s audacity. It was apparent even then this was a turning point in the colonies’ relationship with England. This wasn’t unity for the empire; it was unity against it. Franklin’s Loyalist reptile had officially been appropriated for Patriotic purposes. The meme had officially be coopted. The meaning remained the same, but the context had changed.

Cranky Franky:

So, where was Benjamin Franklin during all of this? He was in London, where he’d been working as a colonial agent since 1757. Though ostensibly there to lobby for American interests, it’s unclear how heartfelt his efforts were at this time, especially since he was fairly loyalty to the crown as late as April of 1776. Sure, Franklin argued against the Stamp Act, telling MPs the tax would piss off already-angry Americans, but Franklin ended up folding pretty easily. “The Tide was, too strong against us,” he later wrote. “We might as well have hinder’d the Suns setting. That we could not do. But since ’tis down, my Friend, and it may be long before it rises again, Let us make as good a Night of it as we can.” [iv] It seems Franklin was ready to go limp to save the empire’s standing.

It’s therefore no surprise that Franklin was irritated when he heard that his “Join, or Die” snake had been coopted for seditious purposes. And he actually learned pretty quickly: in October, from his friend Cadwallader Colden, a colonial official who wrote mostly to throw Parker under the bus: “It is beleived [sic] that this Paper was Printed by Parker after the Printers in this Place had refused to do it…” Shady!

Still, while perturbed, Franklin wasn’t yet completely freaked out. But he would be come November, when he received an irate missive from Massachusetts Lt. Gov. Thomas Hutchinson, an estranged friend from the Albany Congress. The letter’s dated November 18, 1765, after “Join, or Die” had slithered to Philadelphia, New York and Boston, sparking anti-tax rioting throughout the colonies, including right outside Hutchinson’s house. And not only was he pissed, but he blamed Franklin’s drawing: “The riots at N. York have given fresh spirits to the rioters here. … Join or die is the motto. When you and I were at Albany ten years ago we did not Propose an union for such Purposes as these.”

Now Franklin was concerned, and even more so after Parliament held hushed discussions and hearings on the matter, launching investigations unofficial and official alike. [v]

Franklin’s Loyalist rebuttal to the pirated and Patriotic “Join, or Die.”

Eager to distance himself from the “mischievous” misappropriation, Franklin drummed up another cartoon, one he hoped would counter “Join, or Die” and its so-called “Patriots.” Called “Magna Britannia: Her Colonies Reduc’d,” the new cartoon was essentially “Join, or Die” in reverse: Mother England lays prostrate after losing her colonial limbs, while accompanying text argues that England was nothing without her colonies. Without them, she would “slid[e] off the world.”[vi] (As with “Join, or Die” too, this wasn’t an original creation: twentieth-century historian Wilmarth S. Lewis discovered an earlier, 1749 version of this image that is most likely Franklin’s source material. [vii])

Clearly Magna Britannia didn’t catch on. The tide of public opinion had swelled beyond mollification, and England was forced to repeal their unfair levies. Slowly but surely the political situation simmered down, and once again the “Join, or Die” snake receded into the shadows, it’s job done. But it would be back. Bigly.

The Main Event:

It’s 1774. Twenty years had passed since Franklin first created “Join, or Die.” Ten since Goddard brought it back with a vengeance. Aside from a brief cameo in a 1769 pamphlet targeting ousted Massachusetts Gov. Francis Bernard, the serpent had remained out-of-sight; hibernating until it was needed again.

Meanwhile, tensions between England and the rambunctious Americans grew unabated: England enacted more egregious taxes, the most infamous of which was the 1773 Tea Act that sparked in the Boston Tea Party, which led to the retaliatory closure of Boston’s port, which led to even more passive resistance. All this and more made the colonies vibrate with with anticipation of an imminent throw down, and those vibrations in turn stirred the “Join, or Die” snake. It was now wide awake and ready to strike.

The snake reemerged first on the masthead of New-York Journal, on June 23, 1774, in a space once reserved for the British Royal Arms. [viii] Reworked by revolutionary journalist John Holt, himself a former colleague of both Parker and Goddard, the snake was now made of nine parts — since-integrated Georgia had been tacked on the tail — but instead of pleading “Join, or Die,” the motto was, in all caps, “UNITE OR DIE.”

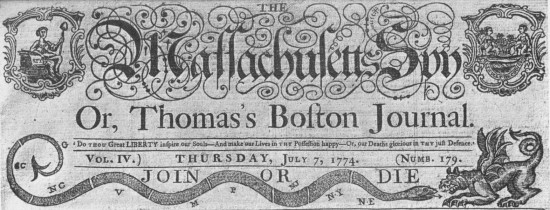

The snake next arose in Boston, where Isaiah Thomas, the publisher of the Massachusetts Spy, paid engraver and radical activist Paul Revere twelve shillings to drum up his own version. Published July 7, 1774, this version of the snake was more elongated, stretching below the Spy’s masthead as it lunged at a small, ridiculous-looking dragon, an intentionally diminutive version of England’s customary symbol.

Then the snake came to William Bradford’s Pennsylvania Journal on July 27, slightly altered but essentially the same: “Unite or Die” remained, but Georgia was now split into two segments. It’s unclear why.

And newspapers weren’t the only ones celebrating “Join, or Die:” Thomas later wrote that pirated copies were being hawked around New York City, Boston and perhaps other towns on the eastern seaboard. But regardless of location or slight alterations that took place there, the mimetic “Join, or Die” message was the same as in 1765: the American colonies must combine or collapse.

These iterations weren’t passing fancies, either: Holt’s Journal version ran until December 8, 1774, when he replaced the linear reptile with a more ouroboros-like creature; Thomas’s Spy maintained Revere’s rendition until April 6, 1775; and the Pennsylvania Journal serpent outlasted them both, keeping “Unite or Die” in its masthead until October 18, 1775, well after the war’s first shots were fired at Lexington and Concord in April. Independence would be declared on July 4, 1776. The world would never be the same.

⌇ ⌇ ⌇

We know how the story ends: the Revolution was won; America was independent; and the States themselves became a meme of a different sort: our quest for equality inspired similar movements in the decades and centuries ahead, most immediately the French Revolution, which is apt, since the catalytic “Join, or Die” snake sprang from French culture in the first place. Memes are funny like that: they can hop continents and generations and remain the same. But only if we the people keep that meaning alive.

Just as Franklin’s snake was inverted in 1765, so too was it almost inverted again: in 1861, when South Carolina confederates tried to coopt “Join, or Die” for their secessionist ends. They were trying to divide the states with the very image that had united them in the first place, a frightening proposition indeed. But we know how that story ends, too: the Union prevailed, proving America’s commitment to its highest ideals of opportunity, inclusion and egalitarianism.

Today, as our nation argues amongst itself over the way forward — open arms or closed fist? — let’s remember the philosophy that made this nation great in the first place: we’re better together than apart. Put another way, unity trumps divisiveness. Or, even more explicitly, The United States of America are meant to be as welcoming and accessible as possible, for all people — and those who say otherwise are just snakes in the grass.

End notes:

[i] Lester C. Olson, Benjamin Franklin’s Vision of American Community, (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2004) pp. 34.

[ii] Olson, pp 38.

[iii] William Goddard, The Constitutional Courant, September 21, 1765.

[iv] Benjamin Franklin to Charles Thomson, July 11, 1765

[v] Olson, 61

[vi] Magna Britannia, Founders.gov

[vii] Wilmarth Lewis One Man’s Education (New York: Knopf, 1967) pp. 455-456.

[viii] Arthur M. Schlesinger, Prelude to Independence: The Newspaper War on Britain, 1764-1776, (Boston: Northeastern University, 1980) pp. 75.

Also, Karen Severud Cook, “Benjamin Franklin and the Snake that Would Not Die,” The British Library Journal, Vol. 22, No. 1 (Spring 1996), pp. 88-111, and Limor Shiftman, Memes in Digital Culture, (Boston: MIT Press, 2014).

Excellent post and took me on a path of learnign even more by looking up ouroboros: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ouroboros

LikeLike

Pingback: Kylie Jenner and The Cult of Self-Made « In Case You're Interested